Two Thai fishermen convicted of raping and murdering, Katherine Horton, a 21-year-old British student on holiday in Thailand, on New Year's Day have had their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment, their lawyer said today, 25th November.

Bualoy Kothisit, 23, and Wichai Sonkhaoyai, 24, were sentenced to death after a speedy trial in January but won a reprieve this month after an appeal. The trial was strongly criticised after Mr. Thaksin Shinawatra, Prime Minister at the time, called for the harshest punishment. The mother of the victim rejected the death penalty saying that such would also be the wish of her daughter.

"The court commuted their death sentences on the ground that they had voluntarily confessed their crime,'' lawyer Prompatchara Namuang said, adding that prosecutors could challenge the court's decision and bring the case to the Supreme Court by December 7.

เรากำลังรณรงค์การยุติโทษประหารในประเทศไทย ซึ่งเป็นหนึ่งในเพียงไม่กี่ประเทศในโลกที่ยังคงใช้วิธีการลงโทษที่ป่าเถื่อนเช่นนี้อยู่

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

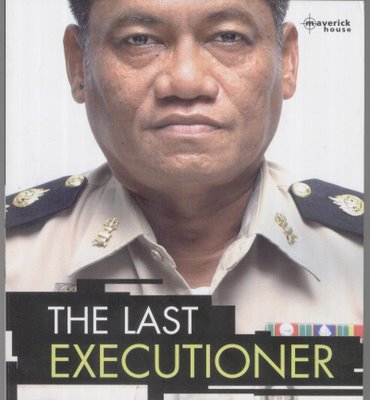

The Last Executioner

The Last Executioner Memoirs of Thailand's Last Prison Executioner by Chavoret Jaruboon

The Last Executioner Memoirs of Thailand's Last Prison Executioner by Chavoret JaruboonThis is a distasteful book. It is a book of no literary merit, little imagination, and little of human feeling. But it tells the story in plain, unadorned language of the most distasteful job on this earth, that of a public executioner. It is an unacceptable job, no one should be called on to carry out judicial murder and made to believe that it is their duty to do so. The task of execution highlights the whole repugnance of the death penalty and the gradual realisation of this is leading to its ultimate abolition.

Chavoret Jaruboon was an ordinary young man who sought the prison service as a stable employment. He was assigned to Bang Kwang, the high security prison in Bangkok where male prisoners condemned to death are detained and where executions are carried out. Others would have kept well away from the death chamber and its rituals but Chavoret wandered in when the machine gun was being serviced and was instructed in its operation by one of the executioners. He must well have realised where his interest would lead. He was recommended to join the team of executioners and progressed through the various levels of responsibility until after ten years he became executioner.

Chavoret's motivation for taking the steps which led to his position are never clearly stated. He obviously has the careful technical ability required to operate a weapon that can give problems, an ability which would not otherwise lead to promotion in the prison service. He is a meticulous person with great control of his feelings and an unquestioning respect for authority, the qualities which certainly led to his selection as executioner. He does not glory in the comradeship of the prison staff but enjoys the regard of his superiors, the chance to perform before the highest authorities, and to make an impression. The 2000 baht fee earned for an execution helps towards the education of his children.

His mental rationalization of his function is a simple one. There are people who are pure evil, "I believe that there are truly bad people who can never be cured of their desire to do depraved things... I believe this type of person deserves to die". Deliberately, he refuses to know the story of the criminals to be executed until after their death lest any personal feeling might affect his efficiency. His duty is to carry out the execution efficiently. Regulations must be complied with but for the rest there must be no delay or mishap which would prolong the agony of prisoner or other participant. Early in the book he repeats his simple belief that the death sentence is justified, and justifies his participation in carrying it out.

It is only at the end of the book that he admits that "killing criminals troubled and depressed me". He has come a long way, "I have come to believe that severe punishment does nothing to solve the problem of crime but it should function as an extreme warning" without seeing the contradiction in this sentence. He reflects further "I believe in karma, which can be bad or good depending on the individual. I never got any pleasure out of shooting people, or out of performing any other role in the persecution process. It was my job". Buddhism gives him the excuse "the convicts on death row are swamped in bad karma and the executioner is doing them a favour by sending them on to their next incarnation for the chance to redeem themselves". It is to his credit that this opinion is quoted from Buddhist monks and he does not adopt it as his own.

Executing 55 men and women in a working life is an abomination. The memoirs of Chavoret Jaruboon are a sad and distasteful story. In the end he cannot justify his choice in life because there is no justification. The value of his story is surely to instruct those who form the chain of command in the justice system that their adherence to capital punishment is also their karma as much as if they pulled the trigger of the machine gun. And so for all of us who acquiesce to this perversity of justice without declaiming 'Not in my name'

'The End of the Death Penalty' refers like the title of the book 'The Last Executioner' to the end of the death penalty by machine gun. Since 2003 Thailand has replaced the machine gun by lethal injection. There are now three executioners where one sufficed before, and the process is no less horrible.

'The End of the Death Penaly' looks forward in hope to the day when this awful practice will truly end.

'The Last Executioner' is available in Asia Book Store

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Conditions of Detention On Bang Kwang Death Row

Prisoners are shackled permanently, shackle chains weigh about 5 kgs

Prisoners are shackled permanently, shackle chains weigh about 5 kgsThere are up to 30 prisoners in each cell, they sleep on the floor in rows

Prisoners spend up to 22.5 hours a day in crowded cells

Ventilation is through a single narrow window which also provides the only lighting

Living in semi-darkness the eyesight of prisoners is affected

Apart from being shackled there is no space to exercise

Drinking water is stale and contaminated

From testimony of prisoners

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Justice Minister who refused to sign death sentences

When Seiken Sugiura was appointed Japanese Minister of Justice last October, he declared his intention of not signing execution orders while in office. He based his decision on Buddhist religious beliefs and philosophy. When reprimanded by the Prime Minister he said that his remarks only described his personal feeling and did not refer to official duties. On Tuesday next he will step down as Justice Minister when Prime Minister Junchiro Koizumi retires.

When Seiken Sugiura was appointed Japanese Minister of Justice last October, he declared his intention of not signing execution orders while in office. He based his decision on Buddhist religious beliefs and philosophy. When reprimanded by the Prime Minister he said that his remarks only described his personal feeling and did not refer to official duties. On Tuesday next he will step down as Justice Minister when Prime Minister Junchiro Koizumi retires.During his year in office Suguira has refused to sign execution orders. He has received both praise and blame for his action.

Surely the act of signing is an act of responsibility, expressed as much in a refusal to sign as it would be in signing.

One legal expert gave support: “The law may expect a Justice Minister to exercise leadership in such decisions, depending on the trends of the times”.

Another commentator claimed that a refusal to sign was a failure to fulfil the duty of Justice Minister.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)